By now, you have used your GitHub repository to add and edit files, to publish a GitHub Page and to fork and edit repositories from your fellow learners. We told you a tiny bit about the "journal" part when using GitHub, but we skipped some very interesting stuff just to keep it simple for the moment. To put things in perspective we should make up for that now and tell you more about Git.

Git and GitHub - partners, but not the same

In this course we started with GitHub. You know by now that GitHub is an online platform to host and share code. GitHub uses Git and adds community stuff around it. So GitHub needs Git, but Git doesn't need GitHub.

What is Git?

Git is a version control system (VCS) - maybe you heard of others before, like SVN or CVS. A VCS keeps track of all changes made to a repository and adds information such as who changed it and when. Revisions can then be compared, restored, and with some types of files, merged.

What is special about Git, is that it doesn't need a remote server to host a repository. Git can be used locally, where it just keeps track of the changes you make to a folder. It also can be used as distributed VCS, so that code is hosted in different locations similar to a peer-to-peer system. Or you can choose to use it like other VCS as a server-client setup, in that case you just choose one of the hosts to act as a server.

The latter is the case when you work with GitHub: You let GitHub host your project, while one or more contributors work on it locally and push changes back to the central repo on GitHub. Now let's get our hands dirty. And, as a reminder: don't hesitate to call out to your coaches for help.

Challenge

Clone your GitHub repository to your computer and keep your repositories synchronized.

Installing stuff

First you should install the tools needed. After that we have a look on how to get a local copy of your GitHub repo. To use git, there are different options:

Git itself is a program without a graphical user interface (GUI), meaning it has no buttons and windows. In this form, you would use it via terminal. There are GUIs though that make Git commands more accessible and add visual aids. Feel free to choose your preferred tool, but we recommend to at least give the terminal a try.

GUI Tools for Git and GitHub with a "normal" click-interface

GitHub is making its own GUI tools for Mac and Windows. You can download them here:

There many many other clients available than those by GitHub. The Git documentation page holds a short list and even more can be found through the Delicious of Matthew McCullough.

If you are a Linux user, you might want to check out this answer on Stack Overflow: Git GUI client for Linux.

The Command Line

If you want to use Git in the terminal, it helps to have done your first steps in Bash before. We would recommend you to start with The CLI Crash Course on Learn Code The Hard Way.

To install Git without a GUI tool, download it here: Git Book.

Code editors

For editing your files you need a suitable code editor. We recommend Sublime Text, which is widely used by many coders of all languages, has a rich ecosystem of plugins and themes and is available for Mac, Windows and Linux.

Sublime Text is free to try, but you need to buy a license after 30 days. If you want to go with something completely free/libre, try

Working locally with Git

Check your Git version

To verify that Git is correctly installed on your system, open a terminal window and type the following (without the dollar sign, that should already be there):

$ git --version

You should see a version number now. If there is an error, please see above to install Git.

Now tell git your name and email address, so that it can add this info to the commits you make. Your email address for Git should be the same one associated with your GitHub account. You propably want to use the same name you use on GitHub too.

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

$ git config --global user.email "your_email@example.com"

Before you clone your GitHub repository, let us explore the basics. Create a folder on your machine called "mylocalrepo". In terminal go to that folder:

$ cd path/to/mylocalrepo

Now initialize a fresh Git repository in this place

$ git init

With this command Git starts tracking this folder.

Now add some files here. Create a file called Readme.md using your favorite editor (e.g. Sublime Text). Until now, Git didn't do much. To add your new files to your repo "journal" you have to explicitly tell Git to take a snapshot now.

$ git add Readme.md

$ git commit Readme.md -m "This is my commit message"

Git has now added an entry to the commit history. Edit your Readme.md again and commt the change. Then tell Git to show the history, or the "log":

$ git log

This will print out the two commits you made, most recent on top. And that's it! Your folder is now tracked by Git and with these few commands you can save your work iterations.

If you use the GUI tools, you can do all this by pressing the right buttons. Sorry to leave you with this, but explaining them in detail would go beyond the scope of this course. If you get stuck, please ask your coaches.

Next, we will get your GitHub repo onto your machine.

Obtain your local copy

Copying a repository from another location is called cloning.

Take a look at your repository on GitHub. In the sidebar to the right there should be a field with an URL, labeled "clone URL". You can use the "HTTP clone URL" for now, but you should read about the details which can be found if you click on the small question mark.

If you use the GitHub GUI, you can just click on "Clone in Desktop". On the terminal, you first change to the folder where you want to put your project files to be, for example:

$ cd /Users/yourname/projects

Then copy the URL shown on your GitHub repository and type the following in your terminal (replace <url> with that URL):

$ git clone <url>

Git will now add a folder for your repository and copy all the files into it. Besides your project files there also will be a hidden folder named .git. That's were Git stores everything it needs for keeping the version history.

Make changes

Did you create a README.md for your repository? If not, do so now locally. While a readme file isn't a required part of a GitHub or Git repository, it is a very good idea to have one. Most projects on GitHub have one and in it you'll find a description of the project and some documentation such as how to install or use it. In this case you might want to add some information about this OpenTechSchool course.

Open the README.md in your text editor, add a link to the course material and save the file.

Now we want to stage it, adding it to the list of files to be committed. Then we commit it with a commit message. In the terminal do the following:

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m 'add link to the OpenTechSchool course material'

This is the same as you did before. Your edit is now ready to be pushed back to GitHub.

$ git push origin master

Git will then ask for your GitHub username and password. "origin master" is the name of the branch you checked out. We will explain that in more detail later.

Now if you look at your repository on GitHub, you will see your README has been updated. In your commit history on GitHub as well as locally you will find your commit with message and everything.

Congratulations! You can now work locally on your code while maintaining a public code base on GitHub!

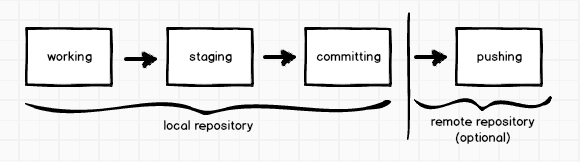

What you just did

Take a short breath, and let us recap some vocabulary.

You init a new Git repository in a given destination.

You then start editing your files, let's just say you add a chapter to an OpenTechSchool course (which would be awesome). When you come to a point when you think the chapter is finished and ready to show to others, there are three steps to make:

- First, you add your changes to a stage, which makes a local snapshot. This separates changes from unchanged files and from changes you don't want to be committed yet.

- After that, you can commit your changes, which marks them as ready to be released and adds an entry in your history. In this step you also add a commit message.

- To finally publish the changes you made to the repository on GitHub, you push the commit (or multiple commits).

You may imagine this workflow as using a shopping cart:

- Put things in (stage) or take things out (unstage)

- Purchase at the register (commit)

- Go back, get and purchase some more items (stage, then commit)

- Take everything home (push)

The separation of these steps provides extra security and control so that you only push the things you really want to be in the remote repository. Furthermore one commit can contain a number of different files. When you edit files on GitHub via the browser, the instant you save a file it gets committed, so saving and commiting on GitHub is the same thing.

When others work on the same repository from their local machines, it is possible that they changed a file while you are working on the same one. To avoid conflicts you would add a step to the beginning of this example workflow: You first fetch the changes from the remote repository (GitHub) so that your local copy is in sync with it. The remote and local changes would then be merged together (often automatically).

More Git:

Stash & Pop

Here is another nice Git trick: Imagine you start working on writing that new chapter. In the middle of it, you get stuck and decide to stop for the moment to switch to another chapter and edit that instead. So you have an unfinished chapter you want to save somewhere - but it's not ready yet to be committed and pushed.

Git provides a very helpful tool that lets you just put things aside for a while, so you have a clean working space without losing anything or being forced to push unfinished work:

- When you stash with Git, it puts the current changes to a safe place.

- To get them back to resume working on them, you pop.

Sounds funny, but really helps a lot. The commands for stashing and popping are as follows:

$ git stash

$ git stash pop

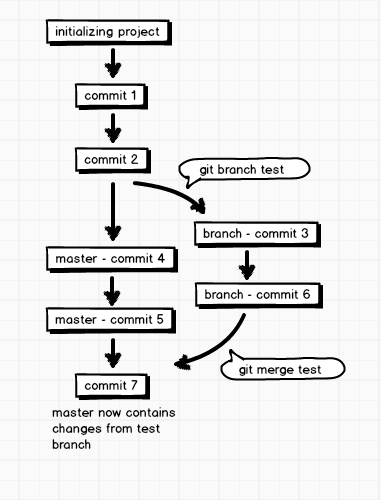

Branching

There's one more thing you should know about Git today. When building software (but also when writing course material) it is common to develop multiple versions of it simultaneously. For example when one version is already released and only bugs or typos are fixed, while another team starts adding new features which will be released later. These are two branches of the same project. By the way, the original thread is also a branch, but it has a special name: it is called master.

You can branch from any point in your version history to create a separate development thread. For example you - want to add a new part to your course material, comprising many new chapters and topics - start a feature branch for this, to keep the main development thread untouched until the whole new part is finished - work on the branch, commiting and pushing as usual. The history and all changes will be tracked by Git, of course - when everything is ready and everyone in your group agreed upon adding it to the next release, you merge this branch back to the master.

Begin by creating a new branch with the name "about-github".

$ git branch about-github

$ git checkout about-github

That's it, you now work on a separate branch. Do some work, add and edit files. Stage and commit, as you did before. When you look at the log, you see all commit messages, including the ones from before you branched off.

You can switch branches easily, but make sure that you have commited everything before you do so. This will get you back on the master branch:

$ git checkout master

When you are satisfied with your new course chapter, merge it back to the master.

$ git checkout master

$ git merge about-github

Now both branches point to the same place in your history. Check the log to see everything aligned neatly.

Wow, this was a lot! And there is so much more. You probably have more questions now, too - don't worry if Git confuses you: this is extra pro stuff.

On codeschool there is a nice small Git learning course. If you want to experiment some more, you might want to try it at Try Git.