Variables¶

Introduction¶

Whew. Experimenting with the angles requires you to change three different places in the code each time. Imagine you’d want to experiment with all of the square sizes, let alone with rectangles! We can do better than that.

This is where variables come into play: You can tell Python that from now on, whenever you refer to a variable, you actually mean something else. That concept might be familiar from symbolic maths, where you would write: Let x be 5. Then x * 2 will obviously be 10.

In Python syntax, that very statement translates to:

x = 5

After that statement, if you do print(x), it will actually output its value

— 5. Well, can use that for your turtle too:

turtle.forward(x)

Variables can store all sorts of things, not just numbers. A typical

other thing you want to have stored often is a string - a line of text.

Strings are indicated with a starting and a leading " (double quote).

You’ll learn about this and other types, as those are called in Python, and

what you can do with them later on.

You can even use a variable to give the turtle a name:

timmy = turtle

Now every time you type timmy it knows you mean turtle. You can

still continue to use turtle as well:

timmy.forward(50)

timmy.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

A variable called angle¶

Exercise¶

If we have a variable called angle, how could we use that to experiment

much faster with our tilted squares program?

Solution¶

angle = 20

turtle.left(angle)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.left(angle)

... and so on

Bonus¶

Can you apply that principle to the size of the squares, too?

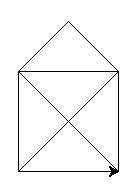

The house of santa claus¶

Exercise¶

Draw a house.

You can calculate the length of the diagonal line with the Pythagorean

theorem. That value is a good candidate to store in a variable. To calculate

the square root of a number in Python, you’ll need to import the math module

and use the math.sqrt() function. The square of a number is calculated

with the ** operator:

import math

c = math.sqrt(a**2 + b**2)